Default Risk Premium

Investors' compensation mechanism for default risk

What is a Default Risk Premium?

A default risk premium is effectively the difference between a debt instrument’s interest rate and the risk-free rate. The default risk premium exists to compensate investors for an entity’s likelihood of defaulting on their debt.

What determines the default risk premium?

Default risk premiums essentially depend on a company or an individual’s creditworthiness. There are a variety of factors that determine creditworthiness, such as the following:

Credit history

If a person or company has regularly made interest payments on time on past obligations, it signals to lenders that the entity is trustworthy. If the entity has taken on incremental debt obligations (i.e., increasing amounts of debt every time debt was taken on) and managed to stay on top of interest payments, lenders will consider the entity more trustworthy as well.

A good credit history inclines lenders to allow the entity to borrow more money, and at lower interest rates. Because the entity’s probability of default is relatively low, the default risk premium charged will be correspondingly low. The opposite is also true. A poor credit history will make lenders demand a higher default risk premium.

Liquidity and profitability

Lenders may also examine an entity’s financial position. For example, if a business is applying for a loan from a bank, the bank might examine some of the business’ recent financial statements. If the business seems to be generating reliable month-over-month revenue, effectively managing costs and producing profits, banks are more inclined to charge a lower default risk premium.

Examining the business’ balance sheet and cash flow statement provides insight into the business’ liquidity and ability to meet monthly interest payment obligations. Conversely, poor liquidity and profitability will solicit a higher default risk premium.

Asset ownership

Assets make borrowers attractive to banks, as the loans can be collateralized against them. For example, if a business owns a $5-million building and would like to take on a $5 million loan to finance its operations, a bank might use the building as collateral. In such a situation, the bank would be able to claim ownership of the building in the event that the business was no longer able to make the loan repayments.

Collateralization commonly underpins mortgage agreements. Banks can take ownership of a property if the borrower fails to make the loan payments. Owning lots of collateralizable assets usually enables borrowers to secure larger loans, but may not directly affect the default risk premium.

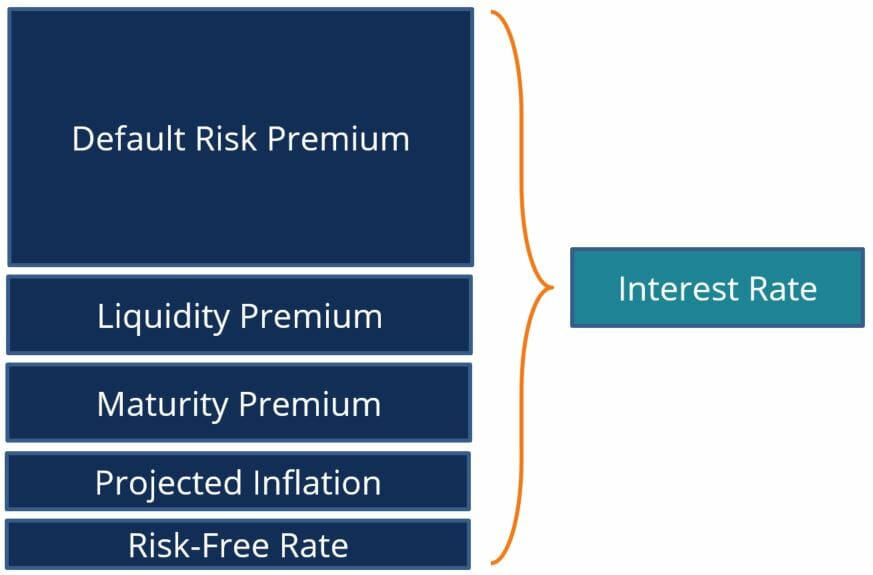

What are the components of an interest rate?

From the perspective of a bond investor, the minimum required return he/she will expect is equal to the sum of the following:

- Default Risk Premium – compensates investors for the business’ likelihood of default

- Liquidity Premium – compensates investors for investing in less liquid securities such as bonds

- Maturity Premium – compensates investors for the risk that bonds that mature many years into the future inherently carry more risk

- Projected Inflation – accounts for the devaluation of currency over time

- Risk-free Rate – refers to the rate of return an investor can expect on a riskless security (such as a T-bill)

More resources

CFI offers the Capital Markets & Securities Analyst (CMSA®) certification program for those looking to take their careers to the next level. To learn more about related topics, check out the following CFI resources: