- What is a Business Commercial Loan?

- Understanding Commercial Loan Structure

- 1. Matching the Loan to the Business

- 2. Collateral: What Stands Behind the Loan

- 3. Balancing Risk: LTV and Amortization

- 4. Pricing the Loan

- 5. Institutional Guardrails

- Types of Commercial Loans

- Requirements for Commercial Financing

- Borrower Requirements

- Collateral & Guarantees

- Loan Terms

- Regulatory & Compliance

- Professional Insights

- Practical Takeaways

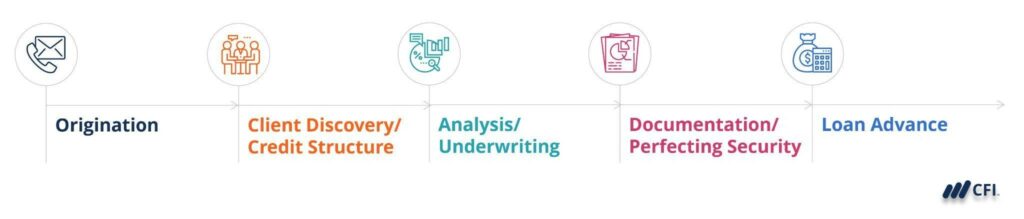

- The Business Commercial Loan Process

- Frequently Asked Questions

Commercial Loans: Structures and Strategies for Smarter Lending

Debt financing to support a predetermined business purpose or expenditure

What is a Business Commercial Loan?

A commercial loan is a form of credit that is extended to support business activity. Examples include operating lines of credit and term loans for property, plant, and equipment (PP&E).

While a few exceptions exist (including commercial property owned by an individual), the overwhelming majority of commercial loans are extended to business entities like corporations and partnerships.

Private businesses with financing needs generally borrow from a commercial bank or credit union; however, they may also seek credit from equipment finance (leasing) firms or other private, non-bank lenders (like factoring companies).

Key Highlights

- A commercial loan is credit earmarked for a specific business purpose or expenditure.

- Commercial loans tend to have much more complicated credit structures than personal loans.

- Three of the most common types of commercial loans are lines of credit, term loans, and commercial mortgages.

- Commercial loans are often secured, meaning that they’re backstopped by physical collateral.

Understanding Commercial Loan Structure

Every commercial loan provider assesses timing, risk, and how a business generates and moves money before approving a loan. Factors that go into the loan include repayment, collateral, and whether the terms fit the company’s cash flow cycle. What makes sense for one borrower might fall apart for another.

A coffee shop preparing for the holiday rush might use a business line of credit that adjusts with seasonal swings. A logistics company buying trucks could take out a five-year term loan, matched to the vehicles’ lifespan and the company’s income stream. Both are examples of commercial loans, but the structure is tailored to each borrower’s reality.

1. Matching the Loan to the Business

Revolving Credit: This is best for variable needs, such as retail stock, receivables gaps, and payroll cycles. Borrowers use what they need and pay it back in cycles, often tied to working capital accounts.

Term Loans: These fund longer-term investments like equipment or commercial property. Amortization schedules might include balloon payments or early interest-only periods to ease initial strain on cash flow.

Example: A brewery expanding its taproom might secure a 7-year term loan with a 15-year amortization schedule, easing pressure in year one while revenue scales.

2. Collateral: What Stands Behind the Loan

Commercial loans require collateral in most cases. Lenders want assurance that there’s something tangible to claim if the loan isn’t repaid. Common assets used as collateral include real estate, equipment, or receivables and inventory:

- Commercial real estate: Up to 75% of appraised value

- Equipment: 50–70%, adjusted for depreciation

- Receivables & Inventory: Often 30–70%, depending on reliability and turnover

Unsecured options exist but are rare — usually offered only to businesses with pristine credit or federal backing, such as through the Small Business Administration (SBA).

3. Balancing Risk: LTV and Amortization

Loan-to-value (LTV) ratios limit how much a lender will issue relative to the asset’s worth. For example:

- A bakery oven valued at $200,000 might support a $120,000 loan (60% LTV)

- A stabilized apartment building might reach 75% LTV

Amortization terms also follow the asset’s life:

- Equipment: 3–7 years

- Real Estate: 15–25 years

The idea is to keep repayments realistic and proportional to how the asset generates income or depreciates over time.

4. Pricing the Loan

Rates reflect risk. Lenders consider:

- DSCR (Debt Service Coverage Ratio): Typically 1.25x or higher

- Collateral quality: A Class A office building holds more weight than secondhand equipment

- Credit track record: Missed payments, tax liens, or lawsuits push pricing upward

Riskier profiles may face more restrictive covenants, like maintaining a set liquidity reserve or prohibiting dividends until the loan is repaid.

5. Institutional Guardrails

No two banks price risk the same, but most have policy boundaries:

- Commercial real estate loans may require appraisals, Phase I environmental reports, and title verification

- Equipment financing usually factors in asset resale value and useful life

- Sector risk caps limit lending to volatile industries like restaurants or early-stage tech

In the end, structuring a commercial loan is about alignment: matching the borrower’s needs to the lender’s confidence. When those two pieces fit, the deal moves.

Types of Commercial Loans

There are many forms of credit available to support businesses, but we’ll look at some of the most common types:

Lines of Credit

An LOC (often referred to as a “revolver”) supports the working capital cycle for firms that sell on credit terms. There is no set repayment schedule; it’s structured to revolve up and down as balances change in the company’s working capital accounts.

Term Loans

Term loans are used to acquire non-current assets, such as equipment, vehicles, and furniture. They are typically amortizing, meaning they reduce with periodic payments (often monthly). At the time of loan advance, both the borrower and the lender will have already agreed upon a repayment schedule. The loan repayment period is generally aligned with the useful life of the underlying asset being financed.

Capital Leases

Capital leases — sometimes referred to as “finance leases” — serve a similar purpose to term loans (meaning they’re used to finance non-current, capital assets like equipment). The main difference between a term loan and a capital lease is that the equipment finance firm funding the lease retains the legal title of the physical asset (as opposed to registering a lien over it).

Commercial Mortgages

Commercial mortgages are another type of term lending, but they’re used exclusively to finance (or refinance) commercial real estate. The analysis and underwriting techniques vary depending on whether the property is owner-occupied or if it’s an income-producing investment property; however, both tend to have more flexible terms (longer amortization, more favorable LTVs, very competitive pricing, etc.) than other types of commercial loans.

Acquisition Loans

Acquisition loans are another category of commercial loans. They are used by businesses that are buying other businesses (or other business divisions) rather than physical assets like property or equipment. While not universally true, acquisition loans tend to have shorter amortization periods and lower loan-to-values than other types of commercial loans.

Requirements for Commercial Financing

Commercial lending decisions weigh risk from financial performance, legal structure, and day-to-day operations. Whether you’re assembling a loan package or reviewing one for approval, knowing what lenders look for helps ensure the deal holds up under scrutiny.

Borrower Requirements

Business Financials:

Most lenders request three years of income statements, balance sheets, and cash flow statements. They evaluate trends in revenue, liquidity (e.g., current ratio >1.2x), and leverage (debt-to-equity ratio).

Credit History:

Lenders often require a personal FICO score above 680 and a business credit score over 75 (e.g., PAYDEX). Past defaults or tax liens can raise red flags, but may be mitigated with documentation.

Loan-to-Value (LTV):

Expect ranges like:

- Real estate: 65–80%

- Equipment: 50–70%

- Inventory/receivables: 30–70% advance rates

Higher LTVs require more substantial cash flow or guarantees.

Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR):

A typical minimum is 1.25x. Borrowers with volatile earnings or seasonal revenue may need to show even higher ratios to qualify.

Loan Purpose & Plan:

Lenders expect a clear breakdown of how funds will be used, including amounts, timelines, and expected ROI. Vague terms like “working capital” should be backed by details (e.g., “inventory restock for Q4”).

Entity Structure:

Legal documentation must confirm the company’s structure, ownership, and signing authority.

Collateral & Guarantees

Common assets put up as collateral typically include real estate, equipment, and receivables. For riskier profiles, lenders may require:

- Personal guarantees from owners with 20%+ equity

- Corporate guarantees from parent companies

Loan Terms

Interest Type:

- Fixed: Common for long-term stability

- Variable: Tied to Prime or SOFR, often lower upfront but riskier long term

Duration:

- 1–3 years for lines of credit or bridge loans

- 5–25 years for real estate or acquisition financing

Longer terms often include covenants (e.g., minimum DSCR or limits on dividends).

Regulatory & Compliance

KYC/AML Requirements:

Lenders verify business identity (EIN, BOI forms) and monitor sources of funds. Industries with high cash turnover face stricter scrutiny.

Supporting Documents:

Licenses, tax returns, insurance coverage, and, in some cases, executive resumes may be required.

Professional Insights

What Underwriters Look For

Strengths:

- Consistent cash flow and margin trends

- Equity investment from the borrower (20%+ for real estate deals)

- Operational experience in the relevant sector

Red Flags:

- Declining earnings

- Overdependence on a single customer (25%+ of revenue)

- Unsettled legal issues

Practical Takeaways

- For lenders: Stress-test collateral values and repayment scenarios.

- For borrowers: Address weak points early. If financials are marginal, consider offering a guarantor or additional security.

A manufacturer might secure a $2M equipment loan at 60% LTV with a 1.30x DSCR, while a startup could pursue an SBA-backed loan with a personal guarantee and business credit cards to support working capital.

The Business Commercial Loan Process

At CFI, we teach the credit process as comprising five distinct steps. These are:

- Loan origination, where the relationship team goes out and prospects for potential borrowing clients.

- Client discovery and credit structure is where the team of lenders (including the relationship manager and the credit analyst) seeks to understand the business’s health, its specific borrowing needs, and how the deal might be structured and priced.

- Analysis and underwriting occur once the team has secured the client’s commitment to proceed with a formal credit application. The bank’s adjudication team (or credit committee) must approve the proposed credit structure at this stage.

- Documentation and perfecting security begins once the deal has been approved, the loan agreement has been executed, and any liens against the business and its assets have been registered correctly by the lender’s counsel.

- And finally, the loan is advanced, and the borrower gets access to the loan proceeds.

Frequently Asked Questions

These are the most common questions borrowers and finance professionals ask about commercial loans:

Is a commercial loan the same as a business loan?

Yes, commercial and business loans are the same type of loan and serve the same business needs. The terms are often used interchangeably.

What credit score do you need for a business commercial loan?

Traditional lenders usually look for a personal FICO score of 680 or higher and a business credit score above 75. Lower scores — down to 600 — may be accepted by alternative lenders if the borrower has strong cash flow, valuable collateral, or SBA backing.

How much do you need to put down on a commercial loan?

Down payments typically range from 10% to 30%, depending on risk, collateral, and loan type. While the specifics may vary, these are generally the required down payments for commercial loans:

- Commercial real estate: 20–30%

- SBA loans: As low as 10%

Borrowers with weaker financials may be asked to contribute more equity upfront.

Additional Resources

CFI offers the Commercial Banking & Credit Analyst (CBCA)™ certification program for those looking to take their careers in banking to the next level. To keep learning and advancing your career, the following resources will be helpful:

Fundamentals of Credit

Learn what credit is, compare important loan characteristics, and cover the qualitative and quantitative techniques used in the analysis and underwriting process.