Belief Perseverance

The inability of people to change their own belief despite the existence of information or facts to the contrary

What is Belief Perseverance?

Belief perseverance, also known as belief persistence, is the inability of people to change their own belief even upon receiving new information or facts that contradict or refute that belief. In other words, belief perseverance is the tendency of individuals to hold on to their beliefs even when they should not. It is an example of bias in behavioral finance.

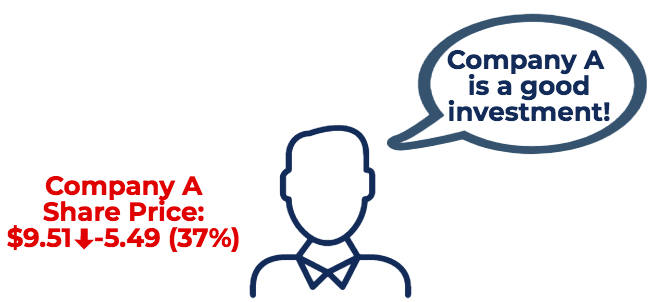

Example of Belief Perseverance

Mike, a 32-year-old financial analyst, is heavily invested in Company A. Over the past few weeks, sentiment regarding Company A has been severely bearish due to major internal accounting fraud. The company’s share price has plummeted to reflect this new information. In addition, other financial analysts are negative about the shares of Company A and assign a low target price. Mike, despite the accounting scandal and significant negative sentiment regarding Company A, refuses to change his belief regarding the company and continues to hold onto his shares in spite of the declining share price. As Mike is sticking to a flawed investment strategy, this is an example of belief perseverance.

Belief Perseverance Biases in Behavioral Finance

There are several major belief perseverance errors. Outlined in CFI’s Behavioral Finance Glossary, they are:

- Conservatism bias: placing more emphasis on old information used to form beliefs rather than on new information.

- Confirmation bias: only noticing information that agrees with old beliefs or perceptions.

- The illusion of control: thinking that you can influence outcomes.

- Representativeness bias: classifying new information based on historic information.

- Hindsight bias: seeing events or actions as predictable despite little or no supporting evidence for predicting them.

Each belief perseverance error will be discussed in detail below.

Belief Perseverance Error: Conservatism Bias

Conservatism bias is a belief perseverance bias in which people fail to incorporate new information and end up maintaining their old views or beliefs.

For example, an investor purchases a security of a pharmaceutical company based on the fact that the company is about to finish stage 3 drug testing and receive regulatory approval. Weeks later, the company announces that the drug failed stage 3 testing and that the approval would be delayed by months, if not years. If the investor clings onto his or her initial valuation of the company and fails to change their evaluation according to the new information disclosed, he would be guilty of conservatism bias.

Belief Perseverance Error: Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias is a belief perseverance bias in which people look for information that confirms their beliefs and exclude information that contradicts those beliefs. Examples of confirmation bias include:

- Only considering positive information about an opportunity or investment and ignoring negative information about the investment.

- Under-diversification in portfolios, as fund managers are convinced that the stock value of a certain company will yield significant returns.

For example, a client of a wealth advisor may insist on adding new securities to his portfolio without considering how the new securities will complement the portfolio and its fundamental value. The client is only doing research that confirms his belief that the securities are of good value without considering the implications on the overall portfolio.

Belief Perseverance Error: Illusion of Control

The illusion of control bias is a belief perseverance bias in which individuals think that they can control or influence outcomes when, in fact, they cannot. Ellen Langer, a social psychologist and professor of psychology at Harvard University, defines the illusion of control bias as the “expectancy of a personal success probability inappropriately higher than the objective probability would warrant.”

For example, a customer service representative who works at his local bank and receives stock options may prefer to only invest in shares of that bank. Since he works at this bank, he may feel that he has some control over the share price. In reality, the customer service representative has virtually no control over the share price of the bank.

Belief Perseverance Error: Representativeness Bias

Representativeness bias is a belief perseverance bias in which individuals use past experiences or information to classify new information. Representativeness bias involves basing decisions on historical trends without determining whether historical information has predictive value.

For example, a company may evaluate its fund managers by placing heavy emphasis on the high returns made over a short period without understanding the probability of those returns happening. The company may hire a fund manager based on his previous performance without considering whether such returns are going to occur in the future.

Belief Perseverance Error: Hindsight Bias

Hindsight bias is a belief perseverance bias in which individuals believe that past events are predictable and inevitable. Hindsight bias is also known as the “knew-it-all-along” effect or creeping determinism.

For example, an investor may claim that the technology bubble in the late 1990s was predictable and obvious. This is an example of the hindsight bias – if it had been obvious at that time, it would not have escalated the way it did and taken so many investors and analysts by surprise.

Other Resources

For more learning, CFI offers an entire course dedicated to Behavioral Finance. To learn more and expand your career, explore the additional relevant CFI resources below: