- Understanding Intrinsic Value vs. Market Value in Finance

- What is Intrinsic Value?

- What is Market Value?

- Intrinsic vs. Market Value: Key Differences

- Real-World Examples of Intrinsic Value vs. Market Value

- Applications of Intrinsic vs. Market Value in Finance

- Common Misconceptions

- Build Your Valuation Skills Beyond Intrinsic vs. Market Value

Intrinsic Value vs. Market Value: Key Differences Explained

Understanding Intrinsic Value vs. Market Value in Finance

Two investors evaluate the value of a company. One calls it undervalued. The other says it’s overvalued. Who’s right?

The answer could depend on whether they’re thinking in terms of intrinsic value or market value. These terms are often mentioned together, but they describe fundamentally different perspectives. Intrinsic value reflects what a rational investor would be willing to pay for an asset, given its risk. Market value depends on the price that buyers and sellers agree on under current market conditions.

Distinguishing between intrinsic value and market value is a foundational skill in finance — especially when you’re valuing businesses or analyzing investments. This guide breaks down what each concept means, how they differ, and why the distinction matters.

Key Highlights

- Intrinsic value represents what a business or asset is theoretically worth based on its fundamentals and future cash flows, while market value reflects what buyers and sellers are currently willing to pay for it in the marketplace.

- Intrinsic value is inherently subjective, varying based on the analyst, methodology, and assumptions used in calculations (particularly in DCF models).

- Market value is objective and directly observable through current market prices, though it fluctuates constantly due to market sentiment and external factors.

What is Intrinsic Value?

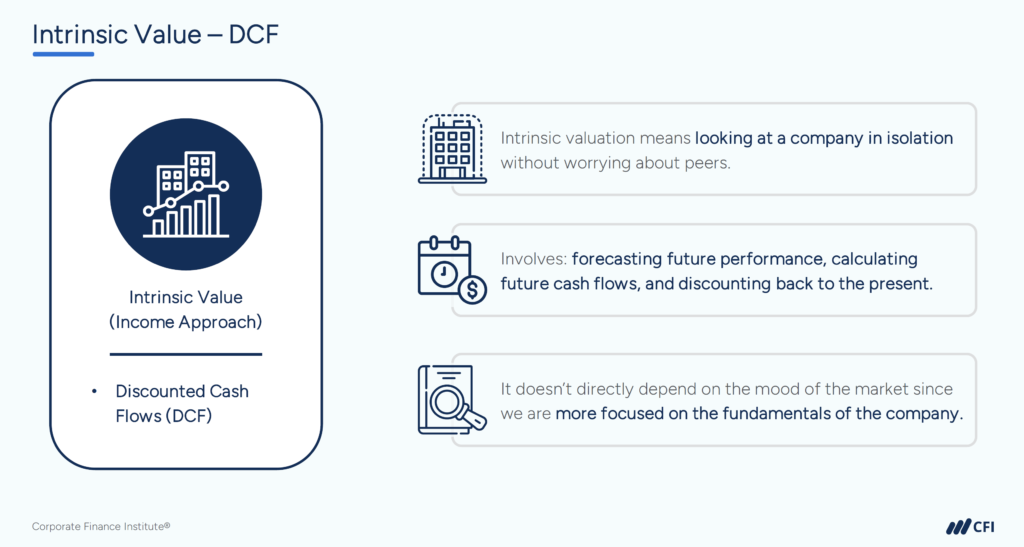

Intrinsic value means the inherent value of a business or asset, or the price a rational investor is willing to pay for an investment, given its risk. It reflects an analyst’s estimate of long-term worth based on the asset’s fundamentals.

Intrinsic value is often calculated using:

- Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) valuation models.

- Analysis of revenue, earnings, and growth potential.

- Asset-based valuation methods, which estimate value based on a company’s net assets (total assets minus liabilities).

Example: If you forecast a company will generate $1 million in free cash flow every year for the next 10 years and discount those cash flows to today’s dollars, you might estimate its intrinsic value to be $8 million even if its market capitalization is currently $6 million.

Because it’s based on assumptions about the future — like projected cash flows, discount rates, and business conditions — intrinsic value is subjective by nature. Analysts using differing valuation methods can arrive at different values for the same asset. It also depends on the inputs they use and how optimistic or conservative their forecasts are.

What is Market Value?

Market value refers to how much an asset or company is generally considered to be worth in a fair market. Market value often reflects, but is not always equal to, the price at which the asset is bought or sold.

Unlike intrinsic value, market value is often inferred from current market prices, especially in efficient marketplaces where prices reflect widely accepted value. Examples include:

- A stock’s current share price on an exchange.

- A property’s most recent selling price.

- A company’s market capitalization (share price x outstanding shares).

Unlike intrinsic value, market value fluctuates constantly. It may rise or fall due to investor optimism, panic selling, or short-term speculation — all factors that have little to do with fundamentals.

Intrinsic vs. Market Value: Key Differences

While intrinsic and market value are often discussed side by side, they come from very different ways of thinking about what an asset is worth.

Here’s a quick look at how these two concepts differ across some key dimensions:

| Definition | The inherent worth of an asset, or what a rational investor would pay given its risk. | The estimated worth of an asset in a financial market under fair and efficient conditions. |

| Basis | Discounted cash flow, or the present value of all expected future cash flows, discounted at the appropriate rate. | Assumes a fair market with no distress, sufficient time and information, and mutual agreement between informed buyers and sellers. |

| Stability | Relatively stable over time (unless assumptions change) | Fluctuates frequently in response to external factors |

| Subjectivity | Varies by analyst, method, and inputs | Objective and observable |

| Example | An analyst values a company at $10mm based on a DCF model, i.e., discounting the estimated future cash flows. | Stock trades at $42/share — the observed market price, often used as a proxy for market value in efficient markets. |

While market value reflects what buyers and sellers are willing to pay right now, intrinsic value attempts to estimate what an asset should be worth based on its fundamentals.

But that estimate is still shaped by assumptions and interpretation — it’s not a universal truth. The difference between the two can reveal potential mispricings, but it also highlights the uncertainty that comes with forecasting.

Real-World Examples of Intrinsic Value vs. Market Value

1. A Stock Trading Below Its Intrinsic Value

Suppose you evaluate a company using a DCF model and arrive at an intrinsic value of $75 per share. But the stock is currently trading at $60. You might interpret this as an investment that you can purchase for less than intrinsic value.

2. A High-Growth Startup That Hasn’t Turned a Profit

A tech startup with no profits might trade at a market capitalization of $500 million, driven by hype or potential. However, its intrinsic value, based on uncertain cash flows and limited assets, might be significantly lower. That doesn’t mean the market is “wrong,” just that it’s pricing in optimism the intrinsic model doesn’t.

Applications of Intrinsic vs. Market Value in Finance

Knowing how intrinsic value and market value differ helps finance professionals make more informed assessments, especially when market prices deviate from what fundamentals suggest.

This distinction matters for:

- Corporate finance professionals, who need a grounded rationale for pricing in mergers and acquisitions (M&A), fundraising, or capital budgeting decisions.

- Equity analysts, who build models to justify recommendations or assess long-term prospects.

- Investors, who aim to identify undervalued or overvalued assets relative to their expectations for future performance.

In practice, the gap between intrinsic and market value may signal both opportunity and risk. A stock trading below your estimated intrinsic value isn’t necessarily mispriced. Your model inputs could be off, or market participants could be reacting to new information you haven’t considered.

Likewise, a high market value doesn’t always mean “overvalued” — it could reflect forward-looking optimism that eventually plays out.

Recognizing this tension is what separates analytical thinking from mechanical valuation. Market value is a snapshot. Intrinsic value is a thesis. Understanding both adds depth to your financial decision-making.

Common Misconceptions

It’s easy to blur the lines between these two concepts. Here are a few myths worth clearing up:

1. “Market price reflects true value.”

Not necessarily. Prices can be driven by hype, fear, or short-term forces unrelated to fundamentals.

2. “Intrinsic value can be calculated precisely.”

It’s an estimate based on inputs and assumptions. Small changes can lead to very different valuations.

3. “If market value is higher than intrinsic value, the asset is overvalued.”

Possibly, but not always. There may be qualitative factors (like strategic value or optionality) that justify a premium.

Build Your Valuation Skills Beyond Intrinsic vs. Market Value

Valuing a company or asset is about forming a defensible point of view on what an asset is worth and why. That’s where the distinction between intrinsic value and market value becomes especially important. Intrinsic value reflects what a rational investor would pay for an asset given its risk. Market value reflects the price set through transactions in a fair market at a specific moment in time.

The ability to distinguish between intrinsic value and market value is a foundational understanding for anyone working in finance. It’s also the starting point for more advanced work in valuation, modeling, and investment analysis.

The most effective way to build valuation skills?

Structured courses, interactive exercises, and guided practice. CFI’s industry-recognized Financial Modeling & Valuation Analyst (FMVA®) Certification equips you with job-ready valuation skills to stand out in today’s competitive market. Hands-on financial modeling experience, interactive courses, and practical case studies prepare you to stand out to employers and on the job.

Additional Resources

Overview of Business Valuation

Learning Valuation: Essential Models, Skills, and Tools for Success