Market Risk Premium

A level of return a market generates that exceeds the risk free rate

What is the Market Risk Premium?

The market risk premium is the additional return an investor will receive (or expects to receive) from holding a risky market portfolio instead of risk-free assets.

The market risk premium is part of the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) which analysts and investors use to calculate the acceptable rate of return for an investment. At the center of the CAPM is the concept of risk (volatility of returns) and reward (rate of returns). Investors always prefer to have the highest possible rate of return combined with the lowest possible volatility of returns.

Concepts Used to Determine Market Risk Premium

There are three primary concepts related to determining the premium:

- Required market risk premium – the minimum amount investors should accept. If an investment’s rate of return is lower than that of the required rate of return, then the investor will not invest. It is also called the hurdle rate of return.

- Historical market risk premium – a measurement of the return’s past investment performance taken from an investment instrument that is used to determine the premium. The historical premium will produce the same result for all investors, as the value’s calculation is based on past performance.

- Expected market risk premium – based on the investor’s return expectation.

The required and expected market risk premiums differ from one investor to another. During the calculation, the investor needs to take the cost that it takes to acquire the investment into consideration.

With an historical market risk premium, the return will differ depending on what instrument the analyst uses. Most analysts use the S&P 500 as a benchmark for calculating past market performance.

Usually, a government bond yield is the instrument used to identify the risk-free rate of return, as it has little to no risk.

Market Risk Premium Formula & Calculation

The formula is as follows:

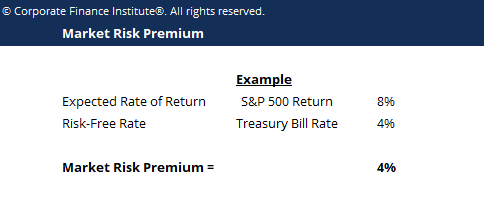

Market Risk Premium = Expected Rate of Return – Risk-Free Rate

Example:

The S&P 500 generated a return of 8% the previous year, and the current interest rate of the Treasury bill is 4%. The premium is 8% – 4% = 4%.

Download the Free Template

Use of Market Risk Premium

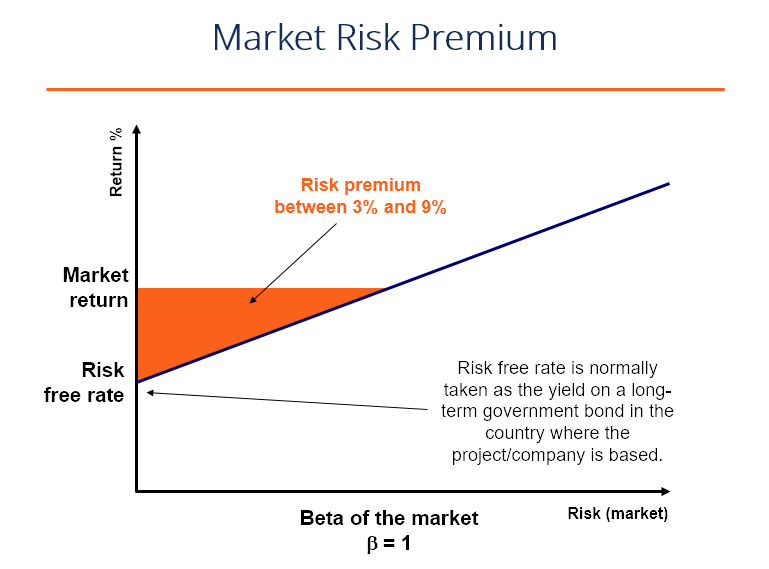

As stated above, the market risk premium is part of the Capital Asset Pricing Model. In the CAPM, the return of an asset is the risk-free rate, plus the premium, multiplied by the beta of the asset. The beta is the measure of how risky an asset is compared to the overall market. The premium is adjusted for the risk of the asset.

An asset with zero risk and, therefore, zero beta, for example, would have the market risk premium canceled out. On the other hand, a highly risky asset, with a beta of 0.8, would take on almost the full premium. At 1.5 beta, the asset is 150% more volatile than the market.

Volatility

It’s important to reiterate that the relationship between risk and reward is the main premise behind market risk premiums. If a security returns 10% every time period without fail, it has zero volatility of returns. If a different security returns 20% in period one, 30% in period two, and 15% in period three, it has a higher volatility of returns and is, therefore, considered “riskier”, even though it has a higher average return profile.

This is where the concept of risk-adjusted returns comes in. To learn more, please read CFI’s guide to calculating The Sharpe Ratio.

Learn More

Thank you for reading CFI’s guide on Market Risk Premium. To keep learning more about corporate finance and financial modeling, we suggest reading the CFI articles below.