- What is a Floating Interest Rate?

- Breaking Down Floating Interest Rate

- Payment Resets vs. Term Changes

- Borrowing Costs and the Yield Curve

- Uses of Floating Interest Rate

- Reference Rate

- How Floating-Rate Payments Change When the Benchmark Moves

- Advantages of Floating Interest Rate

- Floating vs. Fixed Interest Rates Over the Long Term

- Disadvantages of Floating Interest Rate

- Managing Interest Rate Risk on Floating-Rate Debt

- What Borrowers Do When Rates Rise

- Summary

- Additional Resources

Floating Interest Rate

A variable rate of interest

What is a Floating Interest Rate?

A floating interest rate refers to a variable interest rate that changes over the duration of the debt obligation. It is the opposite of a fixed interest rate, where the interest rate remains constant throughout the life of the debt.

Loans, such as residential mortgages, can be acquired at both fixed interest rates and at floating interest rates that periodically adjust based on interest rate market conditions.

Breaking Down Floating Interest Rate

The change in interest rate with a floating rate loan is typically based on a reference, or “benchmark”, rate that is outside of any control by the parties involved in the contract. The reference rate is usually a recognized benchmark interest rate, such as the prime rate, which is the lowest rate that commercial banks charge their most creditworthy customers for loans (typically, large corporations or high net worth individuals).

Payment Resets vs. Term Changes

A changing reference rate affects the cost of borrowing, but it does not automatically change the stated loan term. Most loans keep the maturity date or repayment period the same, and the interest rate simply adjusts at set intervals based on the benchmark.

Where it can get confusing is what happens to repayment:

- In many loans, the payment amount adjusts when the rate changes, while the loan term stays the same.

- In some loan structures, payments do not rise enough to fully offset higher interest costs. In that case, less of each payment goes toward principal, which can slow down repayment and leave a larger balance outstanding later.

If the loan has limits on how quickly the rate or payment can increase, those limits can reduce sudden payment shocks, but they can also change how quickly principal is paid down.

Borrowing Costs and the Yield Curve

Floating interest rate debt often has a lower initial cost than fixed-rate debt when the yield curve is upward sloping. In this environment, fixed rates include a term premium and inflation risk premium because the lender is locking in a long-term rate, while floating-rate borrowers bear the risk that interest rates may rise in the future.

As a result, borrowers may pay less initially with a floating rate, but they assume greater exposure to changes in market interest rates over time. Interest rate risk, for bonds, refers to the risk of rates rising in the future. When the yield curve is inverted, short-term interest rates may exceed long-term rates, which can cause floating-rate debt to be more expensive than fixed-rate debt at origination. However, an inverted yield curve is the exception rather than the norm.

Floating interest rate debt often costs less than fixed-rate debt, depending on the yield curve. In compensation for lower fixed rate costs, borrowers must bear a higher interest rate risk. Interest rate risk, for bonds, refers to the risk of rates rising in the future. When the yield curve is inverted, the cost of debt with floating interest rates may actually be higher than fixed-rate debt. However, an inverted yield curve is the exception rather than the norm.

Floating rates are more likely to be less expensive borrowing in the case of a long-term loan, such as a 30-year mortgage, because lenders require higher fixed rates for longer-term loans, due to the inability to accurately forecast economic conditions over such a long period of time. The general assumption is that interest rates will rise or increase over time.

Sometimes, a floating interest rate is offered with other special features, such as limits on the maximum interest rate that can be charged or limits on the maximum amount by which the interest rate can be increased from one adjustment period to the next.

These features are mostly found in mortgage loans. Such qualifying clauses in the loan contract are primarily designed to protect the borrower from the interest rate suddenly increasing to a prohibitive level, which would likely cause the borrower to default.

Uses of Floating Interest Rate

There are many uses for a variable interest rate. Some of the most common examples are:

- Floating interest rates are used most commonly in mortgage loans. A reference rate or index is followed, with the floating rate calculated as, for example, “the prime rate plus 1%”.

- Credit card companies may also offer floating interest rates. Again, the floating interest rate the bank charges is usually the prime rate plus a certain spread.

- Floating rate loans are common in the banking industry for large corporate customers. The total rate the customer pays is decided by adding (or, in rare cases, subtracting) a spread or margin to a specified base rate.

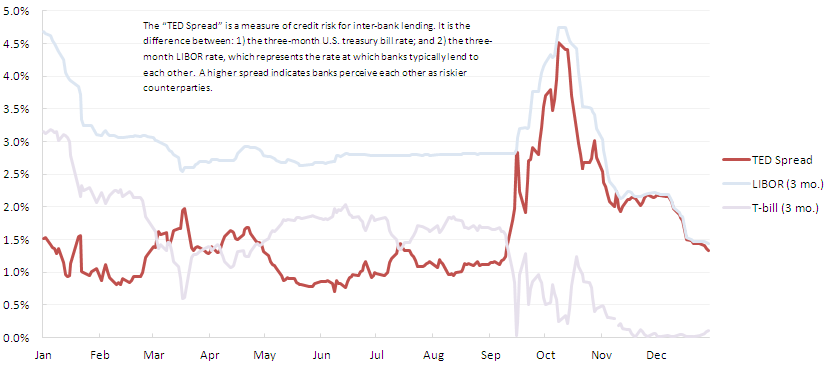

Reference Rate

Changes in a floating interest rate are based on a reference rate, or benchmark. Common benchmarks include the prime rate (used for consumer and corporate lending) and the federal funds rate (often used for short-term lending between institutions), an overnight interbank rate that plays a central role in monetary policy and influences short-term interest rates.

In general, the federal funds rate is not used as a direct contractual benchmark for loans. In most market-based instruments, the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) serves as the benchmark.

The floating rate is typically equal to the selected base rate plus a spread or margin. For example, interest on a loan might be priced at 30-day SOFR + 2%, meaning the rate adjusts periodically based on the prevailing SOFR plus the agreed-upon spread.

Floating interest rates may reset on a quarterly, semi-annual, or annual basis, depending on the loan terms. These benchmarks allow interest rates to adjust with market conditions over time.

How Floating-Rate Payments Change When the Benchmark Moves

When the reference rate changes, the interest rate on a floating-rate loan adjusts based on the benchmark plus the agreed spread. The payment usually does not change every day the benchmark moves. Instead, the loan contract sets adjustment dates (for example, monthly, quarterly, or annually), and the new rate takes effect at the next adjustment.

How the payment changes depends on the loan type:

- Amortizing loans: When the benchmark rises, the interest portion of each payment increases, and the payment amount often increases to keep the loan on track to be repaid over the agreed term. If the benchmark falls, the payment may decrease.

- Interest-only loans: Because the payment is largely interest during the interest-only period, rate changes often show up more directly as higher or lower interest payments at the next adjustment.

In simple terms: benchmark up → rate up → interest cost up → payment usually up (and the reverse when the benchmark declines).

Advantages of Floating Interest Rate

The following are the benefits of a variable interest rate:

- Generally, floating interest rates are lower compared to the fixed ones, hence, helping in reducing the overall cost of borrowing for the debtor.

- There is always a chance of unexpected gains. With higher risk also comes the prospect of future gains. The borrower will benefit if interest rates decline, because the floating rate on his loan will go down. The lender will enjoy additional profit if interest rates rise, because he can then raise the floating rate charged to the borrower.

Floating vs. Fixed Interest Rates Over the Long Term

Over the long term, the choice comes down to payment predictability versus exposure to changing rates. A fixed rate stays the same for the life of the loan, which makes interest costs easier to plan for. A floating rate changes over time, which can reduce borrowing costs when rates are stable or falling, but can increase costs when rates rise.

A Simple Way to Compare Scenarios

A practical way to compare floating and fixed options is to estimate total interest paid under a few interest rate paths. Keep the loan amount, repayment period, and repayment structure the same, then compare:

- a scenario where rates stay roughly flat,

- a scenario where rates rise and stay higher,

- a scenario where rates fall over time.

This comparison helps show where floating-rate borrowing can save money and where it can become more expensive. It also highlights a key practical issue: even if floating rates look cheaper on average, the borrower still needs to be able to handle higher payments if rates rise.

Disadvantages of Floating Interest Rate

The following are the potential disadvantages of a variable interest rate loan:

- The interest rate depends largely on market situations, which can prove to be dynamic and unpredictable. Hence, the interest rate may increase to a point where the loan may become difficult to repay.

- The unpredictability of interest rate changes makes budgeting more difficult for the borrower. It also makes it harder for the lender to forecast future cash flows accurately.

- In times of unfavorable market conditions, financial institutions try to play it safe by putting the burden on customers. They will charge high premiums over the benchmark rate, ultimately affecting the pockets of borrowers.

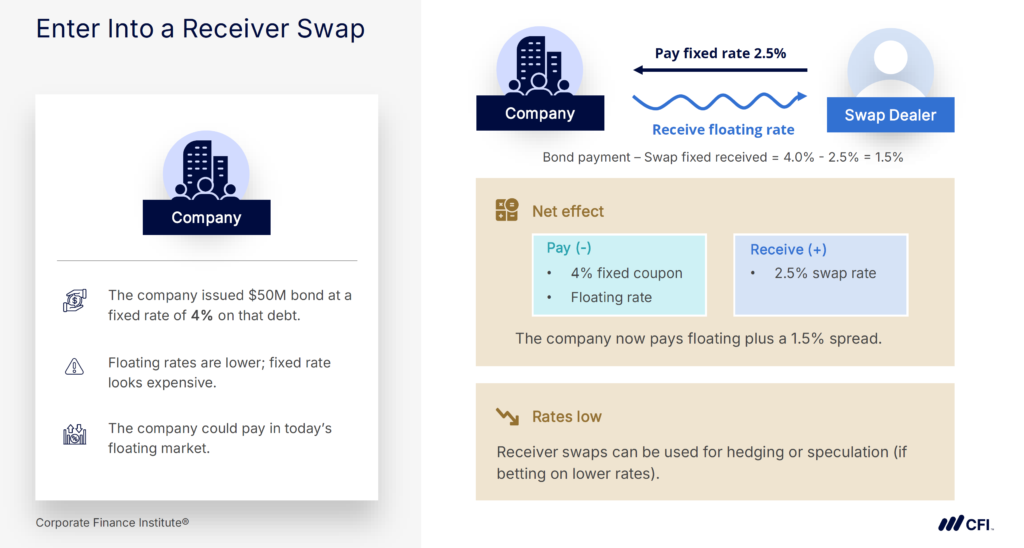

Managing Interest Rate Risk on Floating-Rate Debt

Borrowers who want to reduce exposure to rising interest rates sometimes use financial contracts that offset part of the risk. Common examples include:

- Interest rate swaps: An agreement that exchanges a floating rate for a fixed rate (or the reverse), helping create more predictable interest costs.

- Interest rate caps: Protection that limits how high the interest rate can rise, while still allowing the borrower to benefit if rates fall.

Interest rate futures or forward agreements: Contracts used to lock in or manage expected interest rates over a future period.

What Borrowers Do When Rates Rise

When rates rise, borrowers typically try to either fix the rate or reduce the amount of floating-rate debt. Common actions include:

- Refinance into fixed-rate debt (when terms and market access allow) or use a swap to effectively fix the rate.

- Amend or restructure the facility (extend maturity, adjust amortization, revise pricing mechanics, or add hedging provisions).

- Pay down principal faster to reduce the balance exposed to rate resets.

Shift the funding mix toward longer-dated or fixed-rate sources to reduce sensitivity to benchmark increases.

Summary

Interest rates are among the most influential components of the economy. They help shape day-to-day decisions of individuals and corporations, such as determining whether it’s a good time to buy a house, take out a loan, or put money into savings.

The level of interest rates is inversely proportional to the level of borrowing, which, in turn, affects economic expansion. Interest rates influence stock prices, bond markets, and derivatives trading.

Additional Resources

CFI is the official provider of the global Capital Markets & Securities Analyst (CMSA®) certification program, designed to help anyone become a world-class financial analyst. To keep advancing your career, the additional CFI resources below will be useful: