- What is a Balance Sheet?

- Download CFI's Free Balance Sheet Template

- Balance Sheet Format and Structure

- How Is the Balance Sheet Used in Financial Modeling?

- Importance of the Balance Sheet

- Frequently Asked Questions

- 1. What is a balance sheet in simple words?

- 2. What can a balance sheet tell you?

- 3. What is the purpose of a balance sheet?

- 4. What is the format of a balance sheet?

- Additional Resources

Balance Sheet: Definition, Template, and Examples

A balance sheet is a key financial statement that reports a company’s financial position at a specific point in time.

What is a Balance Sheet?

A balance sheet provides a snapshot of what a company owns (assets), what it owes (liabilities), and the value left for the owners (shareholders’ equity).

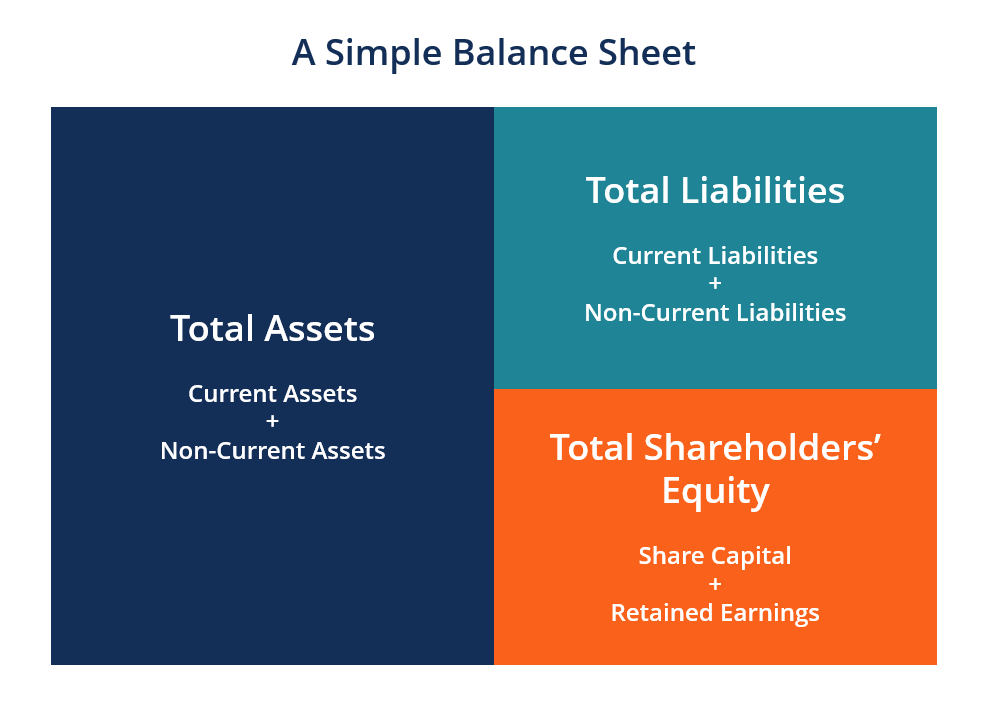

Also called a statement of financial position, the balance sheet is structured around the accounting equation:

Assets = Liabilities + Equity

- Assets: What the business owns, such as cash, inventory, property, and equipment. Assets are classified as current (convertible to cash within a year) or non-current (held for more than a year).

- Liabilities: What the business owes to others, like loans and accounts payable. These are also separated into current (due within a year) and non-current (due after more than a year).

- Equity: The residual interest in the assets after deducting liabilities. It includes owner investments and retained earnings.

The balance sheet must always balance, meaning assets are always equal to the sum of liabilities and equity. As one of the three core financial statements, the balance sheet is used to assess a company’s financial strength, liquidity, and capital structure.

Image: CFI’s Financial Analysis Fundamentals Course

The balance sheet is divided into two sides (or sections). The left side of the balance sheet outlines the company’s assets. On the right side, the balance sheet outlines the company’s liabilities and shareholders’ equity.

The assets and liabilities are separated into two categories: current assets/liabilities and non-current (long-term) assets/liabilities. More liquid accounts, such as Inventory, Cash, and Trades Payables, are placed in the current section before illiquid accounts (or non-current) such as Plant, Property, and Equipment (PP&E) and Long-Term Debt.

Balance Sheet Example

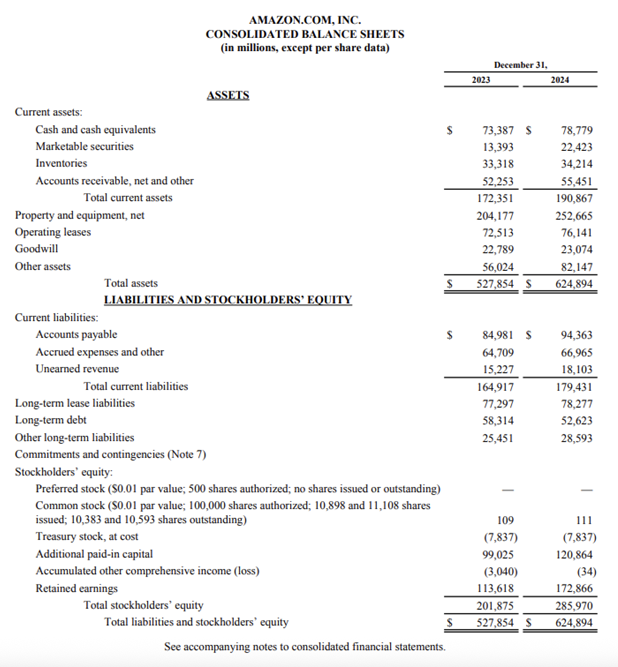

Below is an example of Amazon’s balance sheet taken from its 2024 annual report and Form 10-K filing. Note how the balance sheet starts with current assets at the top, followed by non-current assets, then total assets. Beneath total assets, we find liabilities and stockholders’ equity, which includes current liabilities, non-current liabilities, and finally shareholders’ equity.

View Amazon’s investor relations website to access the full balance sheet and annual report.

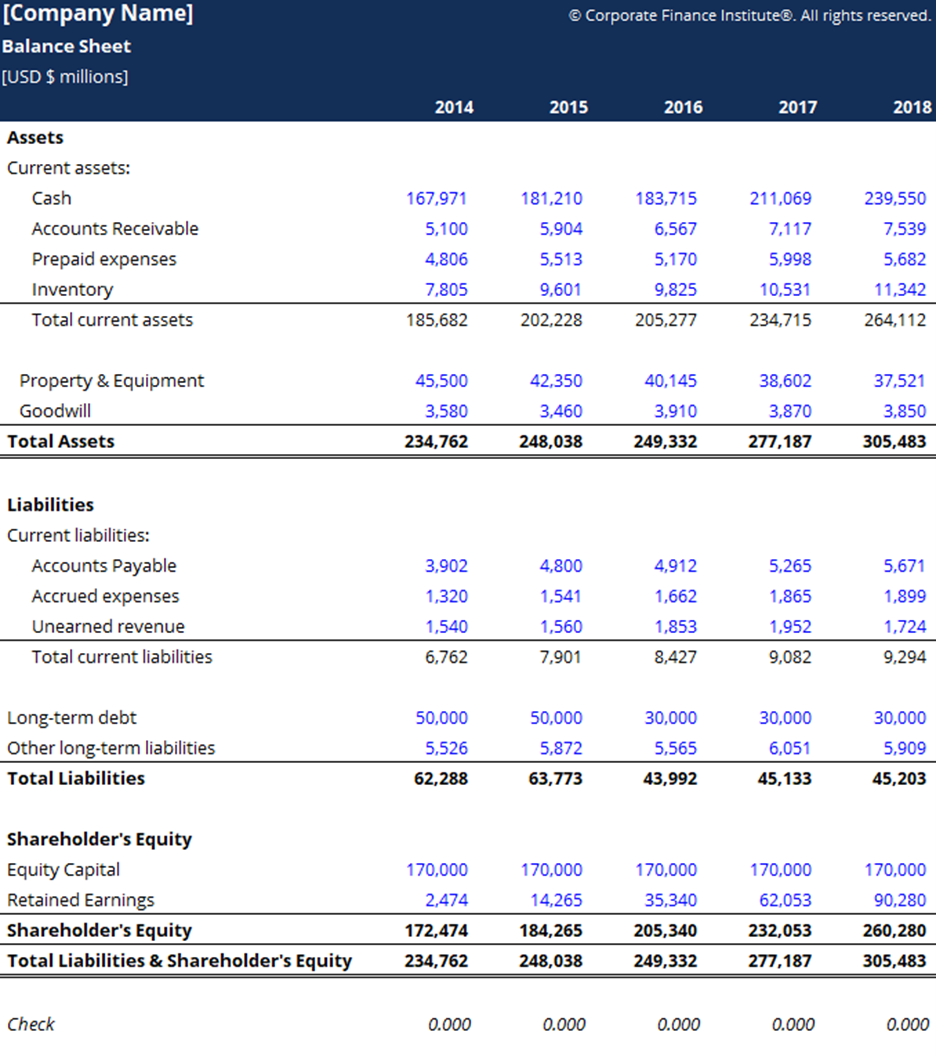

Download CFI’s Free Balance Sheet Template

You can download CFI’s free balance sheet template in Excel to input figures for any company and see how a balance sheet works in real time.

Balance Sheet Format and Structure

Balance sheets, like all financial statements, will have minor differences between organizations and industries. However, there are several “buckets” and line items that are almost always included in common balance sheets. We briefly go through commonly found line items under Current Assets, Long-Term Assets, Current Liabilities, Long-Term Liabilities, and Equity.

Current Assets

Cash and Equivalents

The most liquid of all assets, cash, usually appears on the first line of the balance sheet. Cash Equivalents are also lumped under this line item and include assets that have short-term maturities under three months or assets that the company can liquidate on short notice, such as marketable securities. Companies will generally disclose what equivalents they include in the footnotes to the balance sheet.

Accounts Receivable

This account includes the balance of all sales revenue still on credit, net of any allowances for doubtful accounts (which generates a bad debt expense). As companies recover accounts receivables, this account decreases, and cash increases by the same amount.

Inventory

Inventory includes amounts for raw materials, work-in-progress goods, and finished goods. The company uses this account when it reports sales of goods, generally under cost of goods sold in the income statement.

Non-Current Assets

Plant, Property, and Equipment (PP&E)

Property, Plant, and Equipment (also known as PP&E) captures the company’s tangible fixed assets. The line item is noted net of accumulated depreciation. Some companies will classify their PP&E by the different types of assets, such as Land, Building, and various types of Equipment. All PP&E is depreciable, except for Land.

Intangible Assets

This line item includes all of the company’s intangible assets, which may or may not be identifiable. Identifiable intangible assets include patents, licenses, and secret formulas. Unidentifiable intangible assets include brand and goodwill.

Current Liabilities

Accounts Payable

Accounts Payables, or AP, is the amount a company owes suppliers for items or services purchased on credit. As the company pays off its AP, it decreases by an equal amount in the cash account.

Current Debt/Notes Payable

Includes non-AP obligations that are due within one year’s time or within one operating cycle for the company (whichever is longest). Notes payable may also have a long-term version, which includes notes with a maturity of more than one year.

Current Portion of Long-Term Debt

This account may or may not be lumped together with the above account, Current Debt. While they may seem similar, the current portion of long-term debt is specifically the portion due within this year of a piece of debt that has a maturity of more than one year.

For example, if a company takes on a bank loan to be paid off in 5 years, this account will include the portion of that loan due in the next year.

Non-Current Liabilities

Bonds Payable

This account includes the amortized amount of any bonds the company has issued.

Long-Term Debt

This account includes the total amount of long-term debt (excluding the current portion, if that account is present under current liabilities). This account is derived from the debt schedule, which outlines all of the company’s outstanding debt, the interest expense, and the principal repayment for every period.

Shareholders’ Equity

Share Capital

This is the value of funds that shareholders have invested in the company. When a company is first formed, shareholders will typically put in cash. For example, an investor starts a company and seeds it with $10M. Cash (an asset) rises by $10M and Share Capital (an equity account) rises by $10M, balancing out the balance sheet.

Retained Earnings

This is the total amount of net income the company decides to keep. Every period, a company may pay out dividends from its net income. Any amount remaining (or exceeding) is added to (deducted from) retained earnings.

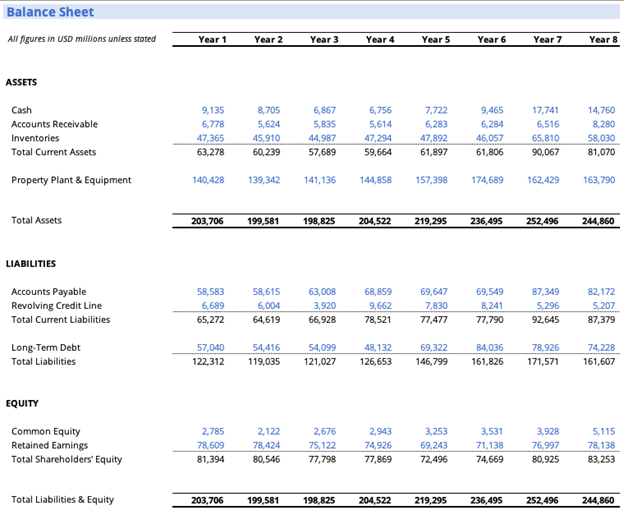

How Is the Balance Sheet Used in Financial Modeling?

The balance sheet plays a key role in financial modeling and analysis. It helps analysts:

- Calculate financial ratios, such as the current ratio, debt ratio, and return on equity (ROE).

- Evaluate a company’s liquidity, efficiency, and financial leverage.

- Use changes in balance sheet accounts to calculate cash flow in the cash flow statement.

For example, a positive change in plant, property, and equipment is equal to capital expenditure minus depreciation expense. If depreciation expense is known, capital expenditure can be calculated and included as a cash outflow under cash flow from investing in the cash flow statement.

Image: CFI’s Financial Analysis Fundamentals Course

Importance of the Balance Sheet

The balance sheet helps you evaluate a company’s financial stability, compare performance with peers, and assess how efficiently the business manages its resources. It also supports deeper analysis when used together with the income statement and cash flow statement.

To interpret a balance sheet effectively, analysts often use financial ratios that link balance sheet data to company performance. Four common categories include:

- Liquidity ratios measure a company’s ability to cover short-term obligations by comparing current assets to current liabilities. Examples include the Current Ratio and the Quick Ratio.

- Leverage ratios let you assess a company’s ability to meet its long-term debt obligations by comparing debt to assets, equity, or earnings. Examples include Debt to Equity and Debt to Total Capital.

- Efficiency ratios measure how well the company uses its assets to generate revenue or cash flow with data from both the income statement and balance sheet. For example, the Asset Turnover Ratio shows how effectively the business converts assets into revenue.

- Rates of Return ratios let you evaluate how well a company generates profits and returns for shareholders by comparing net income from the income statement to assets and equity on the balance sheet. Examples include Return on Equity (ROE) and Return on Assets (ROA).

All of the above ratios and metrics are covered in detail in CFI’s Financial Analysis Fundamentals course.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is a balance sheet in simple words?

A balance sheet is a financial statement that shows what a company owns, what it owes, and the value left for owners at a specific date, giving you a quick snapshot of the company’s financial position.

2. What can a balance sheet tell you?

A balance sheet tells you how strong or stretched a company’s finances are. It shows whether assets can cover debts, how much the business relies on borrowing, and how much value belongs to shareholders. Balance sheets help you assess a company’s financial health, stability, and capacity to handle current and future obligations like debt.

3. What is the purpose of a balance sheet?

A balance sheet helps you understand a company’s financial position at a single point in time. Its purpose is to show what the business owns, what it owes, and the value of owners’ equity. This helps investors, lenders, and leaders assess performance, funding needs, and overall financial strength.

4. What is the format of a balance sheet?

A balance sheet follows a simple format with three sections: assets, liabilities, and shareholders’ equity. Assets appear first, typically organized by liquidity. Liabilities usually list obligations in order of when they’re due. Equity shows owners’ claims. The format follows the accounting equation: assets equal liabilities plus equity.

Additional Resources

To continue learning and advancing your career as a financial analyst, these additional CFI resources will be helpful: