- The Context

- The Reality Check

- The Reflection

- 1. “Character” is key, but it’s a two-way street.

- 2. Communication IS connection.

- 3. Collaboration builds consensus.

- 4. Don’t cave to competitive pressures.

- 5. Financial recommendations and discussions are not abstract or theoretical.

- 6. Challenging relationships are…challenging.

- 7. When the status quo is interrupted, take a deep breath.

7 Relationship Lessons I Wish I Learned Earlier in My Banking Career

Over 1.8 million professionals use CFI to learn accounting, financial analysis, modeling and more. Start with a free account to explore 20+ always-free courses and hundreds of finance templates and cheat sheets.

Kyle’s background is in commercial banking, where he was responsible for originating and underwriting small and middle market credit transactions, as well as managing those client relationships. Kyle has worked with multiple North American-based, diversified portfolios, with industry experience including corporations in manufacturing, technology and e-commerce, hospitality, and professional services sectors. His credit experience ranges from general operating and term lending, to project-based construction financing and succession transactions.

The Context

Every SME lender has been there.

Scenario 1:

Today, for the third time in as many months, a watch report client is late with their margin report. We think: “Does this controller not understand how important compliance metrics are for my performance evaluation?”

Scenario 2:

An accountant we’ve met at several networking events calls. She has a business client looking to finance manufacturing equipment. She wants us to look at the deal and runs through some high-level particulars.

We respond: “Thanks for thinking of me, this sounds super interesting…but the company is much too small for my portfolio. Good luck!”

Scenario 3:

Picking up the phone—once again—to contact that commercial borrower who’s on our overdraft report at least once a week. Reversing those payments really has a way of ruining our morning coffee, right?

The Reality Check

These scenarios have one thing in common. We, as bankers, all succumbed to our own natural (though selfish) instincts around what it means—or should mean—to manage a portfolio of business borrowers. We made “problems” about us, not about the real people on the other side of the table, the people that actually matter in these situations.

Sure, it can be frustrating for us when a client’s reporting is late. But how frustrating—and dejecting—must it be for that business owner to (potentially) be watching years of sweat equity and hard cash unravel right in front of their eyes?

Or that small business we were quick to dismiss? Big or small, that business is how they generate a living and put food on the table for their family. Our language matters.

How about those overdrafts that mess up our mornings? How do you think the owner-operator feels about having to call their vendor or their employee and tell them the cash is no longer on its way?

The Reflection

During my years in banking, I was absolutely guilty of all of the above. And when I say it out loud, it’s easy to feel a sense of shame and regret.

It’s only now, with the benefit of hindsight, more experience, some gray hairs, and a family of my own, that I have a totally refreshed perspective around this (and many other things)!

The good news? If you’re feeling this, too, give yourself a break. It is, after all, human nature to get caught up in the day-to-day. When our livelihoods as bankers rely on our ability to originate new business and maintain a healthy loan portfolio, it’s no wonder we let our more self-serving instincts kick in from time to time. Unfortunately, this can crowd out the human side of what we do, and it prevents us from seeing our client relationships for what they are—relationships.

Not just relationships for the purpose of client satisfaction surveys or new referral opportunities, but real relationships where we have the ability and power to genuinely impact the lives of the business owners we work with, and the lives of the borrower’s stakeholders like employees, customers, suppliers, and many others.

With great power comes great responsibility, so let us not miss the forest for the trees. Here are 7 lessons for client-facing credit professionals that I wish I had learned much earlier in my career. I hope these help some of you avoid having to learn them the “hard way.”

1. “Character” is key, but it’s a two-way street.

As lenders, we’re all well-versed in the 5 Cs of Credit, of which “character” is (arguably) the most important. We’re taught that borrowers with stronger markers of character usually make better, more cooperative clients, which should translate to lower risk of loan loss over the course of the borrowing relationship.

What’s rarely taught, however, is that OUR strength of character—as the face of the client to the bank (and the face of the bank to the client)—is every bit as important. It’s our responsibility to be open and honest with our clients, which sometimes might mean being firm or feeling otherwise uncomfortable. It’s not always easy, but we have to strike the right balance of compassion, professionalism, and objectivity.

As an example, we may feel we’re doing our client a favor by being loose with an overdraft, thinking that returning payments might damage the relationship. What’s likely to be more damaging over the longer term is setting a precedent with the client that’s soft and will surely rub our Risk Management team the wrong way. To DO our job correctly, even when it may be uncomfortable, will help reinforce our strength of character to all stakeholders, both internal and external.

2. Communication IS connection.

Communication is personal. The internet has spawned email, private messaging, audio and video broadcasts, and other forms of asynchronous communication. It takes two to build a relationship, even if creators and followers are not in the same room.

As bankers, we are in the trust business. Earning and keeping trust are inseparable from effective communication. Making genuine connections and fostering them takes effort and skill. Getting important deals or issues resolved means every opportunity to connect is either a building block or a distraction.

Don’t forget that communication is just as critical as our knowledge. Only when we are empathetic and personal can we earn a spot as trusted partners and advisors rather than simply lenders engaged in a series of transactions.

As a general “pro tip” or best practice, difficult news should be delivered in person and (preferably) at the client’s place of business. Think of it as a professional courtesy that the client is on their “home turf” rather than an intimidating boardroom at our firm for what’s likely to be an uncomfortable discussion.

3. Collaboration builds consensus.

Without collaboration, we risk starting every new client relationship on a purely transactional level. It’s all too common for clients to approach the bank with a specific “ask.” They may have a target loan-to-value, interest rate, or a variety of other credit structure elements in mind. This is usually more pronounced with broker deals, since a third party (whose job it is to try and extract ultra-competitive terms from the financial institution) is setting expectations at the farthest end of most reasonable ranges. Many bankers, especially junior bankers, tend to “anchor” on this ask and then, psychologically, feel like anything less is a “loss.”

A much healthier dynamic is to reframe the “anchor” at or near where our firm’s credit policies exist, then work with the client to help them understand the rationale underpinning these guidelines and frameworks.

If it makes good business sense to include one (or even a few) exceptions to policy in the final proposed credit structure, then, even if the deal doesn’t quite meet the client’s original ask, it will still feel like a win, rather than a loss. But most importantly, we will have arrived at the structure through consensus building―which is a much better jumping-off point for a lender/borrower relationship.

Try to avoid immediately anchoring around the specifics of a client’s credit request.

4. Don’t cave to competitive pressures.

Put simply, not every deal is a deal for our firm. In CFI’s courses, we talk a lot about the “risk spectrum,” and some transactions are just too far along that spectrum for a senior lender (in particular). There will always be private, non-bank funding sources available in the market—in fact, it’s a byproduct of a healthy system of capitalism.

But there will also be funding providers whose approach borders on predatory. This is particularly true during periods of rapid economic expansion. Just because someone out there is willing to offer a borrower credit under crazy terms, it doesn’t mean we need to follow suit. In fact, it’s our obligation as a true fiduciary to help the client or prospect understand some of the risks that come with employing excessive leverage in their capital structure.

Being open and honest with the client may help them come to their senses, thus opening the door for us to potentially win the deal under more reasonable terms. At a minimum, we can hope that our compassionate and honest approach builds sufficient goodwill with the client so that we may be able to bid on future business if the borrower is able to weather any present financial risks and actually de-leverage their balance sheet down the road.

5. Financial recommendations and discussions are not abstract or theoretical.

What may feel like a “general” discussion about a borrower’s financial health to us, as lenders, is going to feel a whole lot more personal for the business owner. For example, say you’re conducting an annual review and it’s apparent the business owner needs to cut some costs. We, as lenders, don’t want to start suggesting they consider eliminating X% of their headcount or something like that, even if those numbers make sense.

Headcount = real people, and it’s possible that this business owner cares deeply for those employees and treats them like his or her own family. The borrower is not just a number in our portfolio—the company and its operations are the sum of human employees and stakeholders, living and executing around a shared purpose.

Another common example is when an owner-operated business is offside with a financial covenant. We, as lenders, often say, “Just put some cash in to get back on side.” Well, where is that money coming from? Maybe the owner needs to cash in their retirement account to comply, or perhaps they need to lever up their house just so they can throw more at-risk capital into the business.

Neither eliminating head count nor advancing shareholder loans are abstract courses of action. Being glib in our communication is both inconsiderate and unprofessional.

6. Challenging relationships are…challenging.

When a business and its management/ownership team experience stress, it challenges the banking relationship. As bankers, we are not in the business of making bad loans; however, we understand that loans and relationships evolve over time. When loans become distressed, we must express and impress upon our clients that everyone has an interest in a positive outcome.

Communication can enhance or destroy any potential positive outcomes in a distressing situation. Negotiating with clients in order to address the root causes of business challenges is a task that must be faced together, and it’s a stress test of our skills. It’s also an opportunity for us to step up to a challenging situation and to really support a client in their time of need.

We can gently pull, but not push, on the relationship string. Rarely, and if all else fails, we may “agree to disagree” with clients, and parting ways may be the best course of action for both parties. Generally, the earlier we identify, discuss and understand the root cause of the distress, the easier it is to pull together, solve the issue and avoid such an outcome.

Bankers hate “surprises,” but distressing situations only continue to surprise us if we are not forward, open, and empathetic with our actions. Watch reports, credit restructuring, and special loans teams, and other internal partners are equally important in ongoing client negotiations and risk management. Leverage these partners when it’s appropriate and understand that the process will present challenges—that’s just reality.

7. When the status quo is interrupted, take a deep breath.

The financial services industrial complex loves stability. Extend a loan, auto-withdraw payments on time every month, collect interest income, rinse, and repeat.

But crazy things happen, like overdrafts, missed or late payments, breached covenants, and other forms of technical default. This invariably results in extra administration for our team and us since there’s always a documentation process and difficult discussions to be had.

It’s imperative that we, as lenders, take a deep breath and pause. We must ask ourselves, for how much administrative burden this is going to cause for our team, is it possibly much worse and much more uncomfortable for our client? If the answer is yes (which it almost always is), take the compassionate and human approach, and remember that it’s our job to work through these issues—even if it means time away from business development work or other duties that we may strongly prefer.

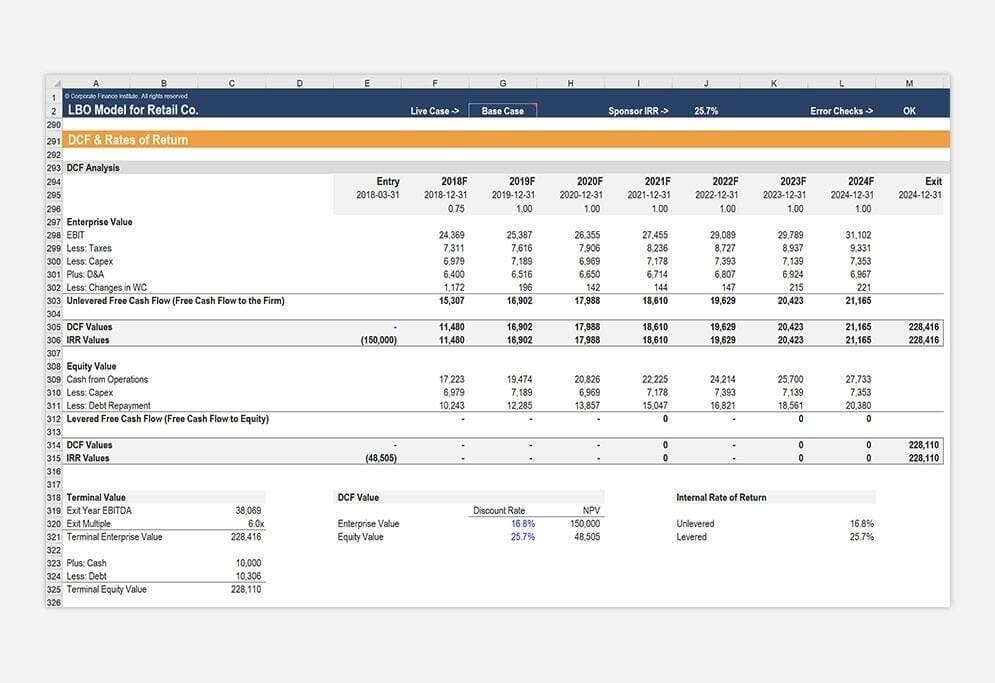

Create a free account to unlock this Template

Access and download collection of free Templates to help power your productivity and performance.

Already have an account? Log in

Supercharge your skills with Premium Templates

Take your learning and productivity to the next level with our Premium Templates.

Upgrading to a paid membership gives you access to our extensive collection of plug-and-play Templates designed to power your performance—as well as CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs.

Already have a Self-Study or Full-Immersion membership? Log in

Access Exclusive Templates

Gain unlimited access to more than 250 productivity Templates, CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs, hundreds of resources, expert reviews and support, the chance to work with real-world finance and research tools, and more.

Already have a Full-Immersion membership? Log in