- What is Financial Accounting?

- Why Financial Accounting?

- How Financial Accounting Works: A Symphony of Numbers and Transactions

- 1. Recording Transactions

- 2. Classifying and Categorizing

- 3. Summarizing

- 4. Communicating, Analyzing, and Interpreting

- The Power of Financial Statements: Landmarks of the Financial Roadmap

- Accounting Methods

- Accounting Principles and Qualities

- Standard Bodies: The Guardians of Consistency

- Unlocking the Power of Financial Accounting: Illuminating the Beneficiaries

- 1. Investors: Seeing Growth Potential

- 2. Creditors: Evaluating Risk and Repayment

- 3. Employees: Ensuring Job Security

- 4. Regulators: Enforcing Transparency and Compliance

- 5. Management: Informed Decision-Making

- 6. Customers: Trust and Accountability

- Key Takeaways

What is Financial Accounting?

Financial accounting is like a GPS that guides users through the land of finance. It’s a systematic process of recording, categorizing, and communicating summaries of the company’s financial transactions and performance to external users, such as creditors, investors, and regulators. The system helps those on a financial journey determine the company’s state (where it is) and make informed decisions (where it wants to go).

In contrast, managerial accounting guides internal users, such as management, in making operational decisions.

Key Highlights

- Financial accounting isn’t just numbers; it’s a business’s journey. As a navigation tool guiding decisions, it helps users model financial trajectories, understand risks, and deploy resources.

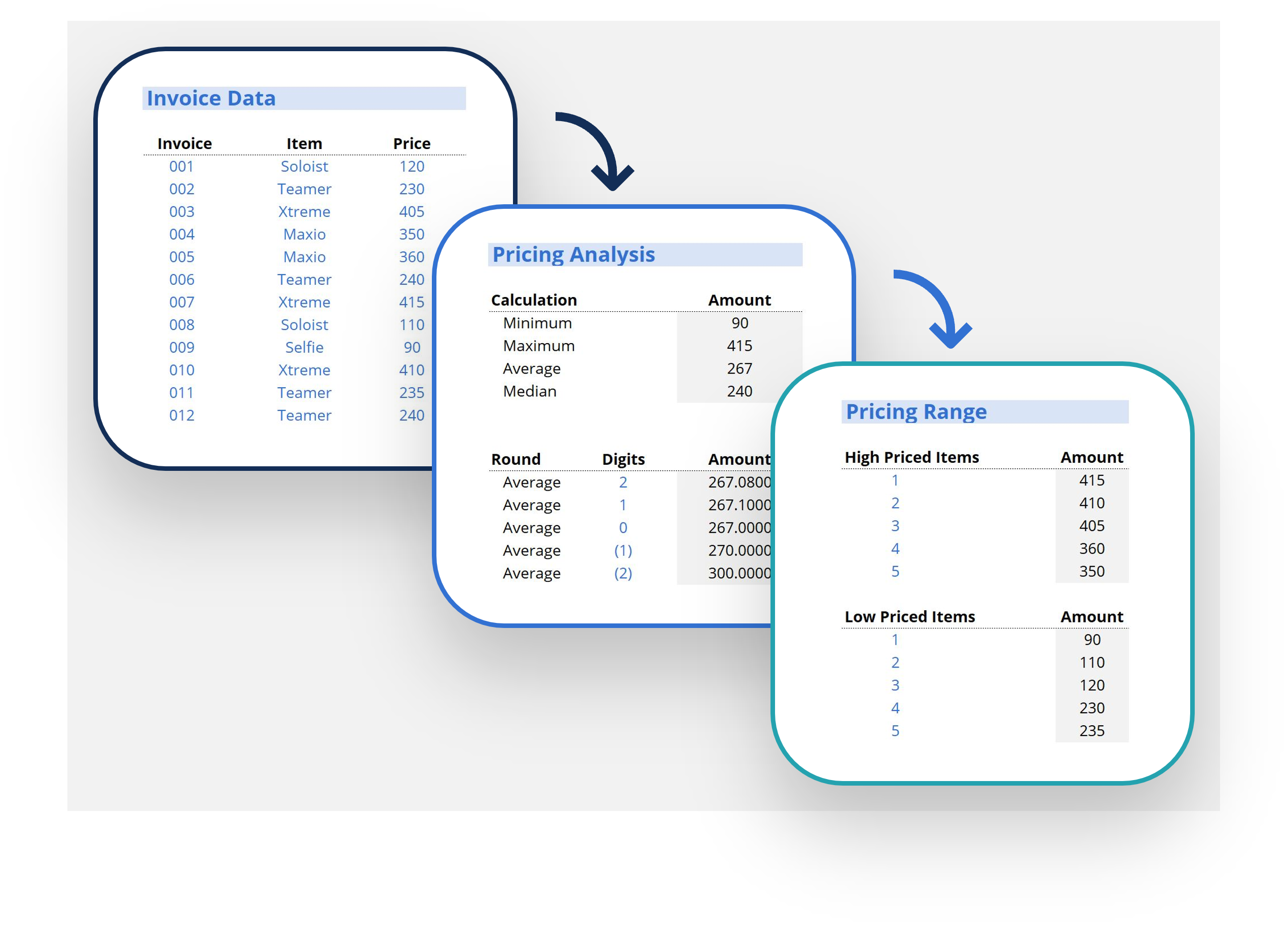

- The Balance Sheet, Income Statement, and Cash Flow Statements form the core of financial reporting. They show company assets, liabilities, profitability, and liquidity, empowering users to make informed choices.

- Guiding principles and standards like GAAP and IFRS help accountants craft reliable reporting. Internal and external stakeholders range from investors deploying capital to regulators enforcing transparency.

Why Financial Accounting?

Have you ever wondered how businesses keep track of their financial health? How do they ensure transparency and accountability in their financial dealings?

The answer lies in the fascinating realm of financial accounting. Follow us on a journey into the mechanics of the financial accounting process, exploring its inner workings and crucial role in presenting a company’s financial story to the world.

Suppose we are considering lending to, or investing money in, a manufacturer for an expansion. We want to decide if the company has generated enough net profit and accumulated the capital necessary to support growth. We aim to understand our credit or investment risks and come to agreeable terms.

The purpose of financial accounting is to offer accountability and transparency. Financial accounting ensures that management is answerable for their financial actions and results.

Financial accounting isn’t just about numbers; it’s about storytelling. It tells us how well a business performs, where it may head, and its access to resources.

Financial statements, such as the income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow statement, provide a comprehensive view of a company’s financial health. Financial analysis gauges the business’s profitability, stability, and liquidity.

A financial accountant can help prepare financial statements, but it’s more than just columns of figures – it’s the narrative of a business’s progression within the business life cycle.

How Financial Accounting Works: A Symphony of Numbers and Transactions

At its core, financial accounting is a systematic process that captures business transactions, organizes them, and presents them in a structured manner.

We can think of a financial accountant as a conductor of a grand symphony, orchestrating a melody of numbers. Crafting financial statements is like composing a musical score. The result is a performance for everyone to enjoy. Here’s a basic breakdown of how it all comes together.

1. Recording Transactions

Every time a business engages in a financial activity, like a sale, purchase, or expense, it must be recorded. These transactions are the building blocks of financial accounting, much like the notes that musicians play.

In our example, when a manufacturer sells its goods, the revenue generated from the sale and the collection of applicable taxes are recorded. Financial accountants specializing in tax accounting can help when sales and other taxes come due. The book of transaction records relies on double entry accounting to drive data consistency.

2. Classifying and Categorizing

To make sense of business transactions, we can organize them into categories, such as revenue, expenses, assets, liabilities, and equity. Classification ensures that each transaction finds its rightful place in the financial landscape. Think of it like grouping brass or woodwind musicians in sections of an orchestra.

For example, cash received from sales is categorized as “sales revenue,” and cash received for taxes is categorized as “sales tax.”

Managerial accounting, or cost accounting, is a branch of this process. The name managerial accounting states that its audience is the management of private companies using it to operate the business.

3. Summarizing

Periodically, usually at the end of a financial period, financial transactions are summarized into quarterly or annual financial statements. These statements provide a snapshot of the company’s financial position and performance during the accounting period. Financial statement reporting includes the balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement. Imagine it as a musical performance.

For example, a goods manufacturer will have a variety of sales and payment categories. These categories can be summarized as “Revenue” or “Expenses” and put in financial statements for a specific period of time. The income statement compiles revenue, expenses, and other financial activities.

4. Communicating, Analyzing, and Interpreting

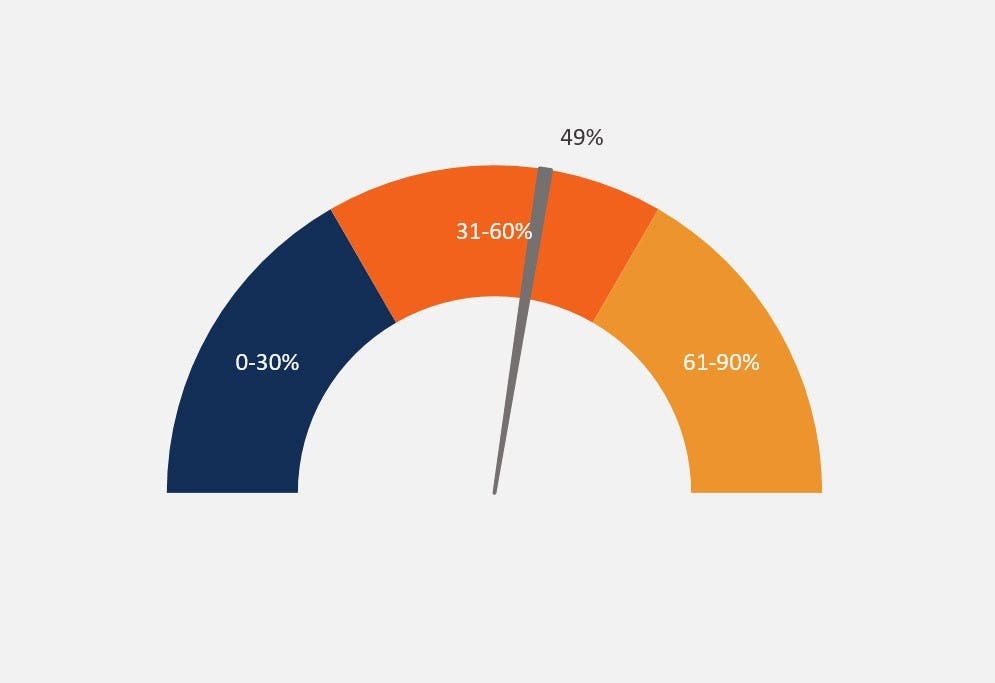

How do stakeholders assess the company’s state of health? They may analyze financial ratios and trends to make informed decisions. This analysis helps us to understand whether the business is profitable and solvent, and to model future cash flows. External parties gauge the level of reliability they want to see, like a symphony’s audience can appreciate the work of the conductor and the orchestral performance.

Suppose our manufacturer wants us, as a potential lender or investor, to be able to rely on the income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow statement to analyze and fund an expansion. The company will want financial accountants to give a quality opinion when preparing financial statements, using standards like Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) set out by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) or other similar bodies. The goal is to meet our expectations when we interpret financial statements.

The Power of Financial Statements: Landmarks of the Financial Roadmap

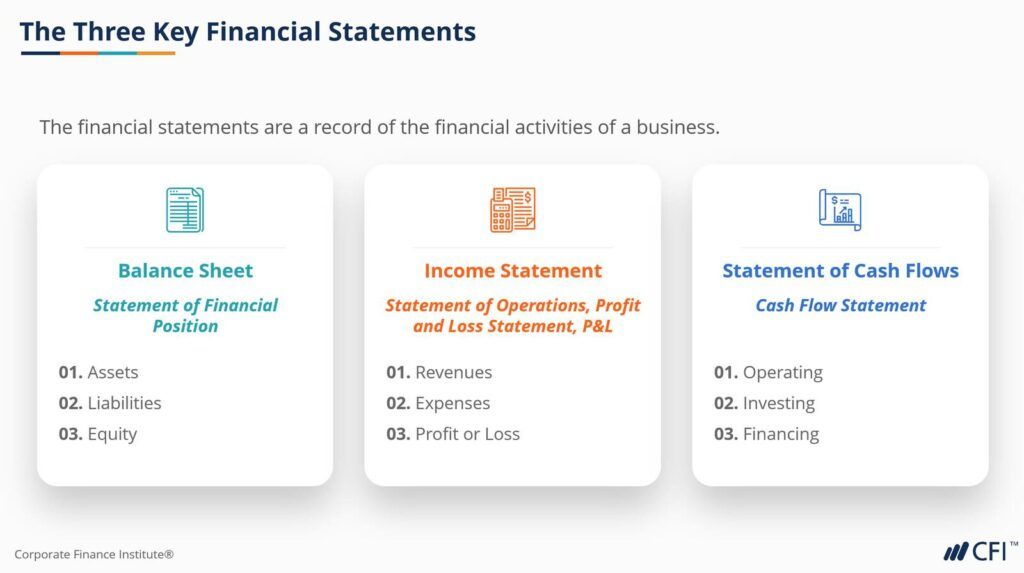

Financial statements are the landmarks of the financial accounting roadmap. They serve as navigators communicating a company’s financial journey to the world. Let’s explore three common financial statements and their significance.

1. Balance Sheet

Balance sheets provide a snapshot of a company’s assets, liabilities, and equity at a specific point in time. Another name is the “Statement of Financial Position”.

Balance sheets capture what the company owns (assets), owes (liabilities), and what remains for the owners (retained earnings and equity accounts). A well-prepared balance sheet showcases the business’s financial stability and capital structure. It may include details sometimes found in a separate statement of retained earnings or shareholders’ equity statement.

Returning to our manufacturing business, which is looking at expanding. Its balance sheet reveals the assets, such as the factory and machinery, liabilities, such as payables and loans, and invested capital from the owner and accumulated equity.

As potential lenders or investors, we may use this financial statement to assess the growth foundation of the business and if investing our capital is acceptable.

2. Income Statement

An income statement lays out the revenues and expenses, culminating with the company’s net income or loss over a period of time. Another name is the “Profit and Loss Statement.”

Income statements show how much the company earned and how much it spent. If using the accrual basis of preparation, we will see revenue and expenses matching up to the same period (and perhaps, not involve cash at all).

Whether we are lending or investing, the income statement reveals the net income after the cost of goods sold, direct costs, and general costs. We can use it to weigh a company’s profitability after operating costs and determine if the manufacturer demonstrates the capacity to repay our debt or provide an income.

3. Cash Flow Statement

Cash flow statements track cash flows that go into and out of companies. They give us insights into what management is doing to generate cash from operations, invest for the future (investing cash flow), and handle financial obligations (financing cash flow).

As a lender or investor, we may want to scrutinize the cash flow statement. Some intriguing spots may be how the manufacturer generates cash from sales of its goods, offers credit to its customers, invests in equipment and other long-term assets, and pays current debts and investors. We may grade management’s cash management strategy and relationships with capital providers that may support the proposed expansion.

Accounting Methods

Let’s compare accounting methods and basic principles to a symphony again – the musical instruments, musicians, and the conductor. We have two broad methods of preparing a company’s financial statements.

1. Accrual Accounting

Accrual accounting relies on the accrual principle and matching principle. We simply want to recognize when economic events occur and match them up best. The accrual basis of accounting coordinates financial transactions to show the business’s rhythm.

We can imagine a conductor directing when each musician plays (a financial transaction or economic event) to orchestrate an experience that exceeds that of individual sounds.

Accrual accounting allows users to experience the financial performance of the business. In this way, an orchestral performance and a company’s financial reports (such as the balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement) are alike.

2. Cash Accounting

This method shows cash transactions as they happen, but not the lasting impact. It limits the depth arising from correctly matching transactions that impact the business similarly. More importantly, if a transaction does not involve cash, this method does not include it. We cannot coordinate all economic transactions with the cash basis of accounting.

Think of individual instruments and musicians. While each is talented and important, unless they are synced up, we cannot experience the depth of the symphony. What happens when there is no conductor or no percussion instruments? The musicians can play together independently, but their sounds and rhythms won’t match a complete performance.

Accounting Principles and Qualities

A symphony performance is emotional—it has “heart.” These principles and qualities form the heart of financial accounting and are rooted in ethical choices. Together, these make financial data reliable and trustworthy—music to users’ ears. The International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) defines two fundamental qualities[1]. The qualities impact the measurement basis we may encounter.

Relevance

The idea is: what can make a difference? Consider the financial records necessary to predict, forecast, or confirm ideas and influence lending or investing decisions. It should help users evaluate the company’s health, performance, and potential future outcomes.

Consider the level of detail we want to use when deciding on a factory expansion. We may want to know how much the total cost of land and construction but not concern ourselves with the costs of the door handles.

Materiality is a narrow aspect of relevance — the idea that when something important is missing due to size or obscurity, the lack of disclosure can make or break our decisions.

Faithful Representation

This is the bedrock of accurate financial statements. The standard requires financial records to reproduce an economic reality “complete, neutral, and free from error.” At the heart of every financial accountant’s duties is presenting factual information.

Financial information cannot be 100% accurate, so we put our “faith” that the preparer can assure us that any human errors and inadvertent omissions are not significant to be material.

Measurement Basis

The two bases are historical cost and current value (including fair value and current cost). Financial accountants balance the principles of relevance and faithful representation when selecting the basis.

Historical cost is often used in financial records; however, it may be more relevant to present the current value of assets that turn over actively, such as marketable securities.

Standard Bodies: The Guardians of Consistency

Imagine a world where a company’s reporting varies drastically from region to region. This chaotic landscape is averted by standard bodies that provide universal guidelines to meet financial and regulatory requirements.

Prominent bodies include the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB), which helps set and align principles and standards internationally, and the accounting bodies of individual countries that are responsible for their respective Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).

1. International Accounting Standards Board (IASB)

The International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) is responsible for global standards known as the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), sometimes called International GAAP. The aim is to bring consistency and transparency, critical for regulatory and reporting requirements across jurisdictions and industries.

Securities regulators draw on this standard to establish order and fair competition. Companies adopting IFRS ensure their financial statements are consistent and comparable across jurisdictions, enabling various stakeholders to meaningfully analyze performance.

2. Domestic Accounting Bodies

The accounting bodies of each country establish domestic standards, for example, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) in the US and the Accounting Standards Board (AcSB) in Canada.

These are known as Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), localized to the requirements of individual countries. While there is an ongoing movement to standardize to IFRS, each country provides options to deviate from international standards to meet local needs.

Domestic users do not always have the need or resources to comply with the rigors of IFRS. Accounting bodies provide a framework for accurate, reliable, and consistent reporting that local stakeholders can also rely on.

In our example, the manufacturer may not need IFRS statements, but it must adhere to domestic GAAP for financial reporting to its lenders and investors. It is a common practice in the country, serving as the basis of business transactions among local users.

In the ever-evolving business world, adherence to these principles and standards ensures a level playing field for companies, lenders, investors, and regulators, wherever they may be.

Unlocking the Power of Financial Accounting: Illuminating the Beneficiaries

Financial accounting is the compass that guides decision-makers through the financial landscape. It can be a treasure trove of insights that benefit various internal and external parties.

From investors seeking growth prospects to employees aiming for job security, and from creditors assessing risk to regulators ensuring compliance, the beneficiaries of financial accounting are as varied as they are essential.

In this section, we’ll tie the purpose of financial accounting to its beneficiaries.

1. Investors: Seeing Growth Potential

Investors believe in a company’s potential. They deploy their capital in pursuit of growth and profit. Financial accounting gives them the financial information to assess a company’s health.

Financial modeling skills, such as those taught by the FMVA program can help analysts evaluate business prospects, including revenue growth, debt levels, and cash flows.

2. Creditors: Evaluating Risk and Repayment

Creditors lend money to companies and can range from financial institutions to suppliers of trade credit. They need assurance that a company can repay its debts.

Commercial lending skills, such as those taught by the CBCA program, can help analysts evaluate a company’s creditworthiness and cash-flow-generation ability to pay back principal and interest. The evaluation maximizes the likelihood of a profitable arrangement between creditors and borrowers.

Suppose a manufacturer buys raw materials from suppliers on credit. Suppliers may review the company’s basic financial statements to ensure their accounts payable can be paid within an agreed-upon period of time.

3. Employees: Ensuring Job Security

Employees invest time, skills, and effort in a company. Financial accounting indirectly impacts them by contributing to the stability and growth of the organization, which in turn affects job security and opportunities for advancement.

Suppose our manufacturer faces labor difficulties due to wage disparity with its competitors. Employees and management can analyze the financial statements and use managerial accounting to engage in dialogue. The goal is to reduce the disparity, preserve jobs, and open opportunities for sustainable growth.

4. Regulators: Enforcing Transparency and Compliance

Regulators, whether government agencies, tax authorities, or industry watchdogs, play a crucial role in maintaining the integrity of financial reporting. They ensure that companies adhere to standards and regulations to safeguard the interests of all stakeholders.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) oversees publicly traded companies in the United States. It relies on financial accounting reports to detect potential fraudulent practices and makes sure accounting rules are followed to maximize transparency.

5. Management: Informed Decision-Making

At the heart of a company’s operations, management generates and relies on financial accounting to make informed decisions. Financial accounting and management accounting serve to guide strategies, investments, and resource allocation.

A manufacturer’s financial reports may showcase products selling well and needing further production capacity. This data-driven decision-making enhances the company’s credibility when seeking expansion of productive capacity.

6. Customers: Trust and Accountability

Financial accounting plays into building customer confidence in a company’s stability and reliability. Accurate reporting reflects responsible business practices, thereby fostering trust.

A manufacturer’s customer is contemplating a long-term partnership. Upon reviewing the manufacturer’s basic financial statements, the customer ascertains that the manufacturer has the experience and capacity to deliver products reliably over time.

Key Takeaways

By interpreting financial statements using financial analysis, many users benefit from a reliable map crafted via financial accounting.

In parallel with managerial accounting, a management’s detailed view of business operations is summarized and communicated to stakeholders to serve their variety of needs.

It’s a testament to the power of transparency, accuracy, and accountability in the world of commerce. As we navigate the world of finance, remember that financial accounting isn’t just about numbers; it’s about people, their aspirations, and the intricate web that connects their interests.

Related Resources

- Analysis of Financial Statements

- IFRS vs. US GAAP

- Bookkeeping

- Accounting Principles and Standards (Course)

- See all accounting resources

Article Sources

Create a free account to unlock this Template

Access and download collection of free Templates to help power your productivity and performance.

Already have an account? Log in

Supercharge your skills with Premium Templates

Take your learning and productivity to the next level with our Premium Templates.

Upgrading to a paid membership gives you access to our extensive collection of plug-and-play Templates designed to power your performance—as well as CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs.

Already have a Self-Study or Full-Immersion membership? Log in

Access Exclusive Templates

Gain unlimited access to more than 250 productivity Templates, CFI's full course catalog and accredited Certification Programs, hundreds of resources, expert reviews and support, the chance to work with real-world finance and research tools, and more.

Already have a Full-Immersion membership? Log in